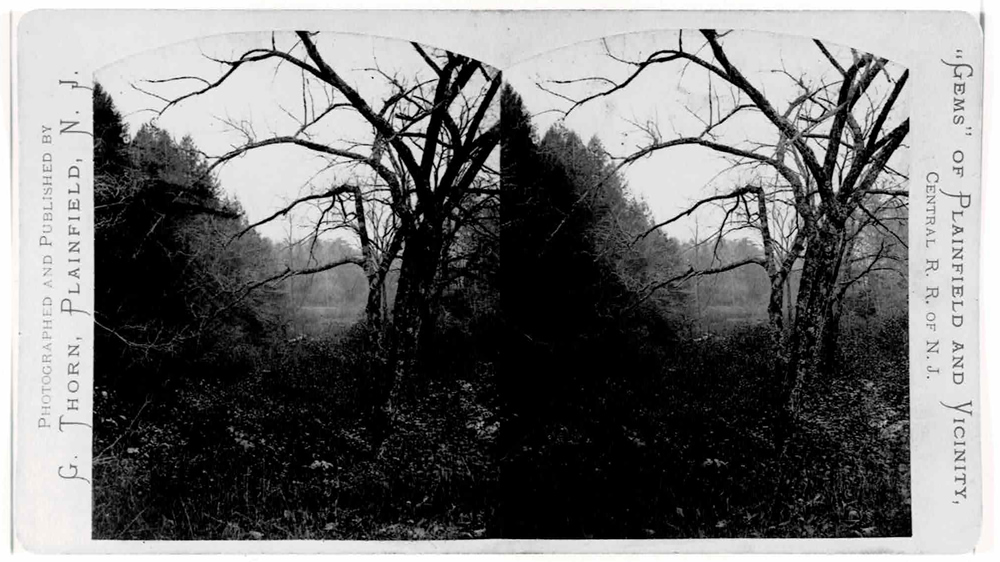

Undated stereograph from the collection of Roger Hatfield with handwritten note on reverse: Vale of Desolation Feltville.

The Persistence of “The Deserted Village,” Part 1

My colleague and friend Matthew (Matt) Tomaso is highly affronted by the name “Deserted Village” as attached to Feltville/Glenside Park, since, as he points out, the village has never been completely deserted. This observation has caused me to look behind the name, since that name has stubbornly stuck to the village, apparently since before 1876, when it was reported as already long-standing in a series of tourist photographs featuring the village. Many places have become physically deserted without attracting such local fame for that characteristic. How did Feltville become so firmly known as the Deserted Village?

I have had a lot of fun looking at the article which most offends Matt—and which, to my mind, exemplifies the arc of my historic research, since it suggests more questions than it answers. Yes, I am having fun with a “primary” source of sorts (although newspaper articles may be in some nebulous primary area, but this one purports to be a report on a personal visit). Elizabeth Shepard’s long rambling article entitled “A Deserted Village” was published in the Boston Evening Transcript on November 7, 1888. Ms. Shepard was from the Boston area, nowhere near Feltville, and had gained local fame for travel pieces. In 1893, she would publish A Guide-Book to Norumbega and Vineland: The Archaeological Treasures Along Charles River, so it is clear she had something of an interest in lost places.

Perhaps one of the most telling items of Shepard’s 1888 article as exemplifying the persistence of the name, the Deserted Village, is where we all found the article. None of us found it doing newspaper research—perhaps largely because although it purports to be a travel piece, it appeared in a newspaper in Boston, Massachusetts, a place where one would not expect readers to be looking for a tourist destination in New Jersey. All of us researching the village found it in the Appendices to The Felt Genealogy: A Record of the Descendants of George Felt of Casco Bay, John E. Morris, compiler, first published in 1893, as we were researching David Felt, who built Feltville.

Indeed, the article is one of two newspaper articles referenced in the same genealogical entry on David Felt. Both of the articles celebrate Felt not for his creation and successful operation, for 15 years, of an entire mill village, but for his leaving and the village’s “desertion.” To me, at least, this seems more than a little ungenerous—or downright mean—on the part of the author of the genealogy. But, perhaps this has more to do with the persistent identity created by the name “the Deserted Village” than anything else.

I hope you, too, have fun with my dissecting of this “primary source.”

A Highly Romanticized Article

Elizabeth Shepard was not the first person to call Feltville “the Deserted Village,” when her article entitled “A Deserted Village” was published in the Boston Evening Transcript on November 7, 1888. In the article, Shepard purports to report on a seemingly serendipitous visit to the Deserted Village of Feltville, far from Boston, in New Jersey.

As noted, the genealogy also includes a portion of a newspaper article reporting on the sale of “a real deserted village:”

New Jersey has a real deserted village among the mountains of Union County, which was sold the other day at auction. Forty years ago a New York stationer, named David Felt, bought 600 acres of the wild land there, which included a water privilege, built two paper mills, a church, schoolhouse, and store, and a fine house for himself, and a lot of cottages. . . . now it presents a scene of desolation, with buildings falling to pieces, and the costly machinery covered with rust, and an old man named Thompson the only resident of this place. The whole village was sold by order of court, and Warren Ackerman bought for $11,450 what cost Felt $200,000. Ackerman owns the adjoining property, and will probably use or sell this for summer residence purposes.1

Thus, are David Felt’s years of operating a thriving mill village reduced to a footnote to the failures of others at the site.

The Warren Ackerman named in this article probably knew a bargain when he saw one, and an opportunity to add to his huge collection of New Jersey properties. There is no indication that Warren Ackerman was influenced in his purchase by the name—Deserted Village—so firmly and gleefully referenced by the unknown author of this article. But, in spite of having had several successful careers, in spite of being one of the wealthiest men in New Jersey, and certainly one of its biggest landowners, it is the ownership of the “Deserted Village”—and to a lesser extent, its successful conversion into a resort—for which Ackerman is remembered. The “Deserted Village” made whatever fame both David Felt and Warren Ackerman enjoy.

In reporting on her visit, the Shepard article presents questions and mysteries on any number of levels. How did a writer born and educated in Boston end up meandering into the Deserted Village, and then persuading a Boston newspaper into publishing the article she wrote about her visit? My research has turned up clues to the how Shepard may have actually gotten herself to the Deserted Village, which is somewhat at odds with what the article suggests.

In a book of Memorial Tributes to Abraham Coles published in 1892, a year after Abraham’s death, by his son Jonathan Ackerman Coles, a tribute by Elizabeth Shepard is featured. There, Shepard describes numerous visits to Abraham’s estate, Deerhurst, in Scotch Plains, and the gift by Abraham of one of his published works to Shepard.

Abraham was the brother in law of Warren Ackerman, purchaser of the Deserted Village. So, while Shepard’s article represents her as setting out to find a village which simply fascinated her, it is far more likely that the visit was pre-arranged through Abraham.

With that artifice in mind, it is even more fun to examine the various elements Shepard’s article contributes to the myth of the “Deserted Village.”

Shepard sets out with unnamed company to find the village she had been hearing about—“on the very outskirts of civilization, with flourishing cities and towns all about it, little seems to be know of the ‘deserted village,’ and few comments are made by those who have visited it.” She stops to get directions from a stranger on the way:

One autumn day I drove to the tavern in Scotch Plains, N.J. to have my horse watered and to make inquiries of the good old colored man who performed the office. My question seemed to amuse him. “Sarted village!” said he, with a chuckle which shook his sides. “Doan’ know no’sarted village roun’ yere. Guess yo’ mus’ mean Feltville.”

“Yes, that is the name,” said I, and thereupon he gave me such lucid directions that I could not go astray.

Stopping a minute to consider that at least some part of this encounter took place (likely within the context of Shepard knowing already where she was headed, and having obtained permission), I like to think that the old gentleman who Shepard inserted as a crucial character actually might have said “Doan know no’sarted village roun’ yere. Guess yo’ mus’ mean Feltville.” I suspect that, as Matt Tomaso has pointed out, this individual recognized that the village called “deserted” was only so in the popular imagination, and actually was a place where people still lived—by now, some of the people that Warren Ackerman had brought into the village.

Continuing on, Shepard and her companions start an ascent up the Watchung Mountains, passing a “guide-board, plainly marked ‘Feltville,’ standing sentinel at the corner.”

Shepard interrupts her trip narrative to give us some history of Feltville, going through a description of how Felt created the village, and a litany of some of the failures since. When she picks up her narrative again, it is to say the following:

Slowly winding our way past the tumble-down buildings and two or three scattered farmhouses, a level bit of road brought us to a large rustic gate, flanked by the formidable sign, “No trespassing under penalty of the law.” However, we found that the gate would open, and so we ventured.

Again, this bold disregard for property rights seems something of an artifice, when we consider Shepard’s prior acquaintance with Abraham Coles, and likely, through Coles, with Warren Ackerman.

Once through the gate, our self-reported trespassers encounter no people, and wander about, peeking into windows, including into the “mansion,” which “had not yet been disturbed.” Inside the mansion, they spy fireplaces and falling plaster, and bookshelves with “more the appearance of a decayed museum than a bookcase,” noting: “These glimpses were obtained in a most cursory manner, over yawning chasms or from piazzas whose condition threatened one’s disappearance into unknown regions.”2 The details seem chosen to underscore the impression of a “deserted” village, although Shepard does note that other cottages in the village were apparently in better repair, having been refurbished by the recent purchaser, “Mr. Ackerman of Scotch Plains.” She goes on to insist:

But if the village was no longer in a dilapidated condition, it was almost as nearly deserted; and if robbed of some of the romance, it had been only partially awakened from its deep slumber.

Just as they are about to leave, the group meet “an urchin, who proved a valuable acquaintance.”

During our conversation, he asked me if I had been to the old burying ground. Upon answering in the negative, he offered to show me the way, and scrambling down dale and up hill we found ourselves in a little corner of “God’s Acre.”

“Two girls were drowned up to Felt’s Lake one time,” said my little guide, “and there’s where they are buried,” pointing to two small stones which bore no trace of an inscription.

Poor girls, they sleep, their graves unkept and forgotten, but mayhap containing a romance as tender and sweet as any yet recorded.

Shepard imagines that the various trees in the old graveyard are growing from “the hearts of the sturdy pioneers.” Only one readable gravestone is still standing.

Their new friend directs them on to a scenic ravine which reminded Shepard of “the boldness of Colorado scenery.” Interestingly, around this time, Thomas Moran, later famous for his dramatic paintings of western scenery, was producing rather romanticized drawings of Feltville; Moran will be the subject of a future post.

The article ends with a flourish:

As the big gate slowly swung upon its hinges, we felt it shut us out of a little world, with a history all its own.